George Banks and all he stands for will be saved. Maybe not in life, but in imagination. Because that's what we storytellers do. We restore order with imagination. We instill hope again and again and again.

— Saving Mr. Banks

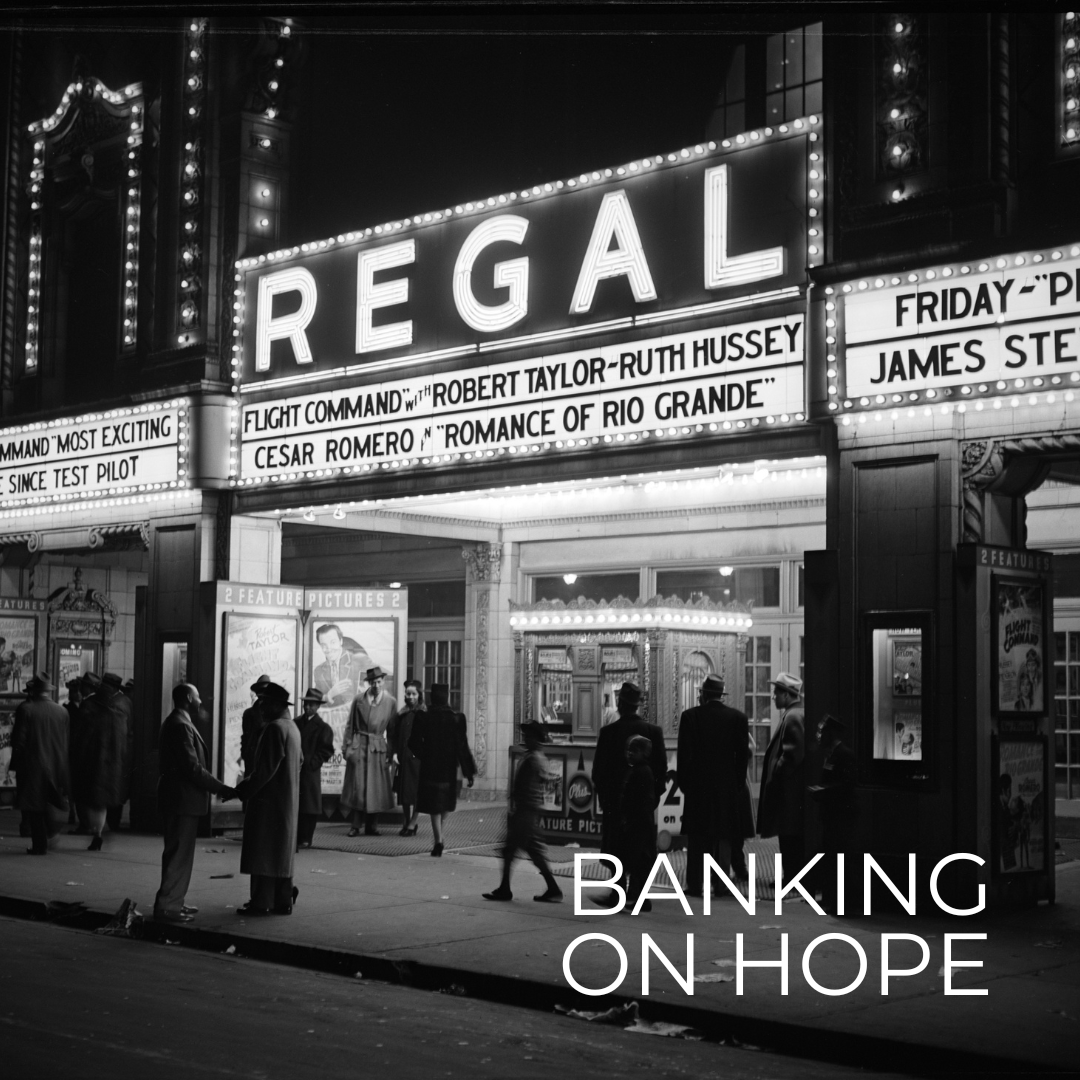

I saw Walt Disney's Mary Poppins as a little kid in an enormous movie house—the Windsor Theatre in Houston's Galleria area—before the Galleria was even a thing. I recall Dick Van Dyke dancing with animated penguins and the happy ending with the kites in the sky before Mary floats away with her umbrella. I also remember a few years later, not too far from the old Windsor after they'd built the Galleria, standing in a line wrapped around the shopping center's indoor ice skating rink to see a new movie that had just come out called Jaws. Based on the not-too-subtle movie poster and the buzz, I knew it concerned a giant man-eating shark, and yet, in the end, it too had a happy ending (at least for most of the characters). Not long after that, I was queuing up again around the same ice skating rink to see another movie—another one with a happy ending. One called Star Wars.

I love movies, enjoy a variety of cinematic genres, and welcome all sorts of storylines, but I admit I'm partial to the happy ending. I don't need every loose end tied up with implausible perfection, but when I sit through a film that ends sadly, cynically, or without any sense of redemption at all, I usually find myself disappointed. I leave asking, "With all the real sadness, trouble, and defeat in the world, why did I just spend the last two hours of my life in the theater absorbing more of it?"

Saving Mr. Banks is a movie released in 2013 which tells the story of author Pamela "P.L." Travers and the pursuit of the screen rights to her Mary Poppins books by Walt Disney. The title of the film refers to George Banks, the father in Travers's Mary Poppins stories whose family the irrepressible Mary comes to serve and eventually save with her enchanting magic, charming personality and catchy show tunes.

As the movie proceeds—through a series of flashbacks to Miss Travers' childhood in Australia in the early 1900?s—we begin to sense that the Mr. Banks' character in her books, a banker, is based upon her loving, creative but deeply depressed real-life father, also a banker, whom she adored despite his addictions. In fact, we later learn that Travers' real name is Helen Goff and that she's taken her deceased father's first name, Travers, as her pen name. We learn also that when she was seven years old, just before her father died, her bright-eyed but no-nonsense aunt had come to live with her family, taking charge of their troubled household. Though she could not save Travers' father, as we follow her aunt's manner, notice her turn of phrases, and spot her umbrella, we're left to conclude that she's the inspiration for Mary Poppins herself.

Near the end of the film, still trying to convince her to trust him, Disney empathetically speaks to Miss Travers about her childhood and her loss, sharing evocative details of his own hardship growing up in Missouri and his complicated relationship with his own dad. He urges her not to let the failure to save her own father in real life prevent them from turning a story born of personal tragedy into one of redemption.

"In every movie house, all over the world," Disney tells her, "in the eyes and the hearts of my kids, and other kids and their mothers and fathers for generations to come, George Banks will be honored. George Banks will be redeemed. George Banks and all he stands for will be saved. Maybe not in life, but in imagination. Because that's what we storytellers do. We restore order with imagination. We instill hope again and again and again."

There's something mystical about the healing power of art. And stories with happy endings, whether in the form of magical fairy tales, epic adventures on the high seas, science fiction space operas, or even compelling biographical pictures, have a way of making hope seem more credible to us. Of setting things right inside of us. Such stories help us sort out the chaotic real world in which we live. They give us a picture—though it might not always happen—of what we feel deeply in our souls should happen. And embracing just the possibility that things can turn out right, somehow not only demonstrates our capacity for hope but steels our conviction that, in the end, they will.

God — Help me bank on hope. Amen.

— Greg Funderburk