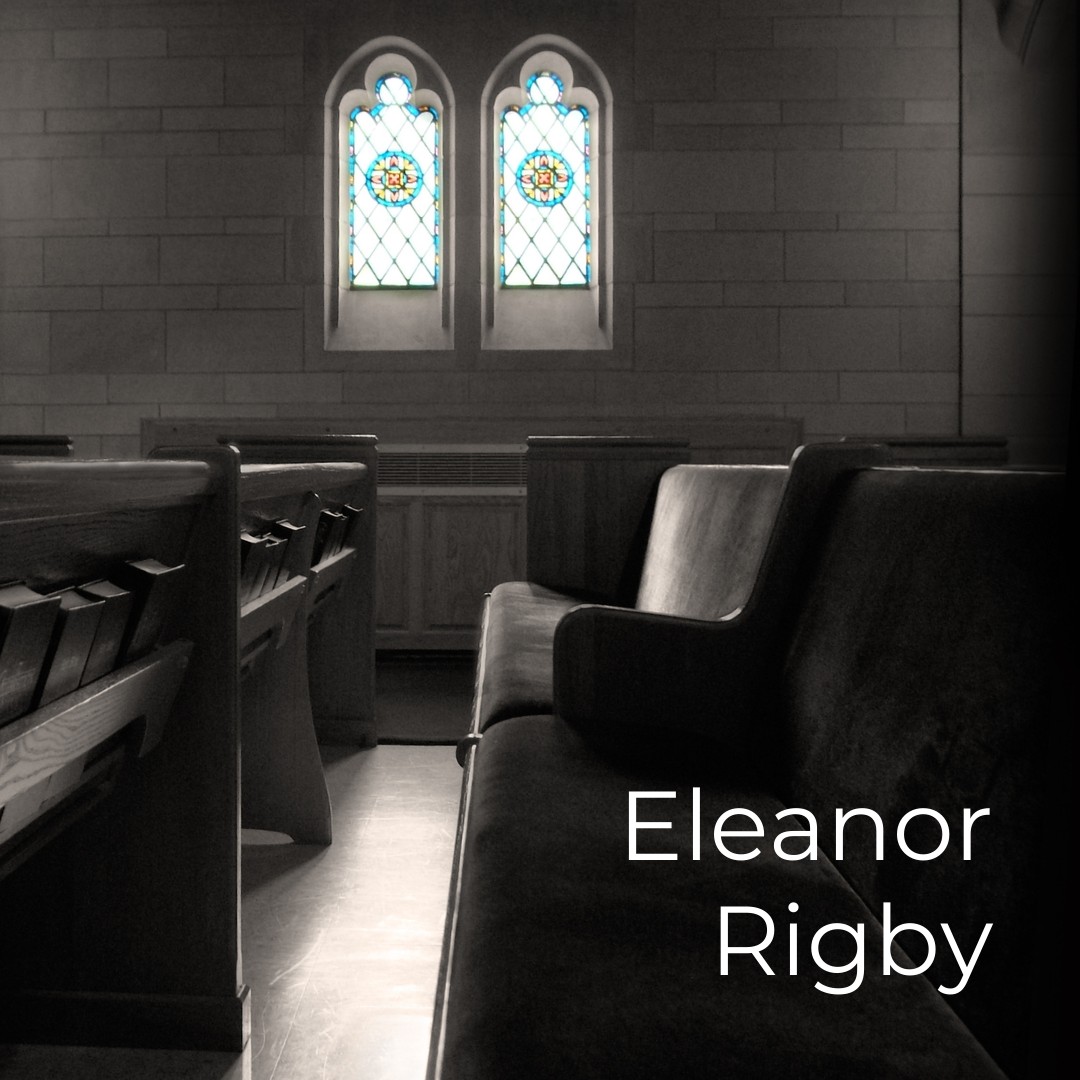

Eleanor Rigby picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been....

All the lonely people, Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people, Where do they all belong?

— Lennon, McCartney & Harrison, "Eleanor Rigby"

Robert Putnam is a really smart social scientist. Over two decades ago, in his book, Bowling Alone, Putnam asserted that we, as a society, have been growing ever more disconnected from each other. In his writing, he popularized the term and notion of "social capital." Social capital is our stock, our reserves, our network of connections with colleagues, friends, and even casual acquaintances which provide us—wired as we are as human beings—with the sense of security, belonging, meaning, hope, and happiness we all need in our lives. Social capital helps us to avert the sort of despair the Beatles sang about in their poignant 1966 song "Eleanor Rigby."

Putnam's exhaustive research, interviews, and data show us that we now belong to fewer organizations, reach out to our neighbors less, meet with friends less, and even socialize with our families less than we used to. We're even bowling alone—hence the title of his book.

Father McKenzie, writing the words of a sermon

that no one will hear, no one comes near....

All the lonely people, Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people, Where do they all belong?

Edmund Burke was an Irish-born statesman, economist, and philosopher who served in the British House of Commons between 1766 and 1794. He wrote and spoke prolifically on the development of human virtue, stability in a culture, and how to develop a government that might redound to the benefit of all its people. Most interestingly, he insisted that the effort in all of these realms must start on a small scale from the bottom up.

To love the little platoon we belong to in society is the first principle—the first link—in the series by which we proceed toward a love of mankind. Those without a little platoon are going to suffer from a diminished love of mankind, and those places where the platoon is absent are going to be places of anxiety.

"For two years," John Leland of The New York Times wrote recently, "you didn't see friends like you used to. You missed your colleagues from work, even the barista on the way there. You were lonely. We all were." Leland's article then goes on to describe what neuroscientists tell us happened to our brains during the last two years. Was it bad? Well, it wasn't good.

Look, probably by now, no one needs to tell you that being isolated increases your risk of depression, anxiety, and addiction. No one needs to remind you that researchers at Brigham Young found that the psychological effects of loneliness correlate closely with the physical effect of smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Or that weak social networks reduce your immune response, putting you at a higher risk of heart disease, cancer, stroke, hypertension, and dementia. We've all heard and read this by now. We just need to know how to fix it.

Well, consider everything bigger than your family, but smaller than the government—what are you a part of? The number of community institutions you're connected to goes a long way in predicting your well-being. As you continue to regain your footing in a post-pandemic world this summer, perhaps consider not diminishing, but increasing your involvement in the community institution that delivers the most meaning to you. Lean into that one—whatever it might be.

And now—a quick public service announcement:

-

Regular participation in a religious community is clearly linked with higher levels of happiness. (Pew Research Center, "Religion's Relationship to Happiness, Civic Engagement, and Health Around the World," 2019)

-

Even if one holds little stake in the sacraments and sermons, social science research indicates that resilience benefits accrue from simply being an active part of a congregation regardless of one's lack of or struggles with faith itself. (Tim Carney, Alienated America, 2019).

-

Healthy marriages and religious attendance are closely correlated with each other and church-going kids have measurably better relationships with their parents, other adults, and their peers. (Robert Putnam, Our Kids, 2015).

-

For someone at the median national income of $56,500, spending two or more hours devoted to religious activity in a given week is associated with more happiness than getting a $20,000 raise. (American Time Use Survey in Robert Putnam and David Campbell, American Grace, 2012).

It's terribly interesting that Lennon and McCartney set their lament about loneliness largely in an empty church. If church were a drug, our doctors would be prescribing it for our loneliness. They might even put it in the water.

All the lonely people, where do they all belong?

— Greg Funderburk