For as long as human beings have dwelt together, we’ve insisted on placing art in the public spaces we inhabit. Going back to cave drawings on the walls of caverns in France dating from 30,000 years ago to the ancient ruins of Greece and Rome, to the “metallic bean” Cloud Gate installation in Chicago, or the faux Prada Shop located along a desolate highway in West Texas, we human beings seem compelled to place art in and on our way. While some of it is designed simply for the sake of beauty or to create a compelling point of interest in a landscape or urban space, more often the purpose of public art is to remind us of some important civic idea or a crucial human virtue to which we ought to aspire.

The city of Reykjavik, Iceland, is full of public art installations, but whether one is strolling the paths of one of the city’s many well-manicured parks, waiting on a sidewalk to cross a busy intersection in the center of town, or standing in front of a soaring church or multi-story government building, it is impossible to miss the work of Einar Jonsson. His sculptures are everywhere.

Born in 1874 on a farm in southern Iceland, Jonsson as a youngster traveled to Denmark to train at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, then worked in Italy in the early 1900s before returning to his native Iceland. He plied his trade mainly in the medium of plaster due to the fact that modeling clay was almost impossible to find in his country at that time.

Jonsson’s subjects and themes draw mostly from Norse mythology, Icelandic folklore, and a mystical form of Christian spirituality. Often populated by angels, trolls, and bold, beautiful, and fiercely-chiseled human figures, his sculptures all have names that touch on something primordial in our psyches—names like Protection, Grief, Dawn, Tree of Life, Earth, Fate, Spirit and Matter, Breaking the Spell, and Guardian Angel.

In 1909, in his mid-thirties, Jonsson offered to donate all of his sculptures—those completed and those yet to come—to Iceland’s government in exchange for a working studio and a museum to house all of his existing and forthcoming creations. Construction soon began on the museum, a large working area for Jonsson, and an apartment in which he would live with his wife, Anne Marie. It all opened in 1923. Jonsson continued to work there up until the time of his death in 1954, but it was only toward the end of his prolific career that his plaster works were cast in bronze, making them more durable and suited for outdoor display.

And while Jonsson’s art can now be seen all over Reykjavik, his work is most densely concentrated in a single place—a soul-stirring sculpture garden dotted with birch trees and stone located in the shadow of the museum that bears his name. There one can view The Wave of Ages, an astonishing bronze angel rising from stormy waters with her head turned to the clouds; a massive, evocative, and somber work intriguingly called Memorial to a Lost Airliner; and an entrancing and thought-provoking sculpture known as Thor Wrestling with Age.

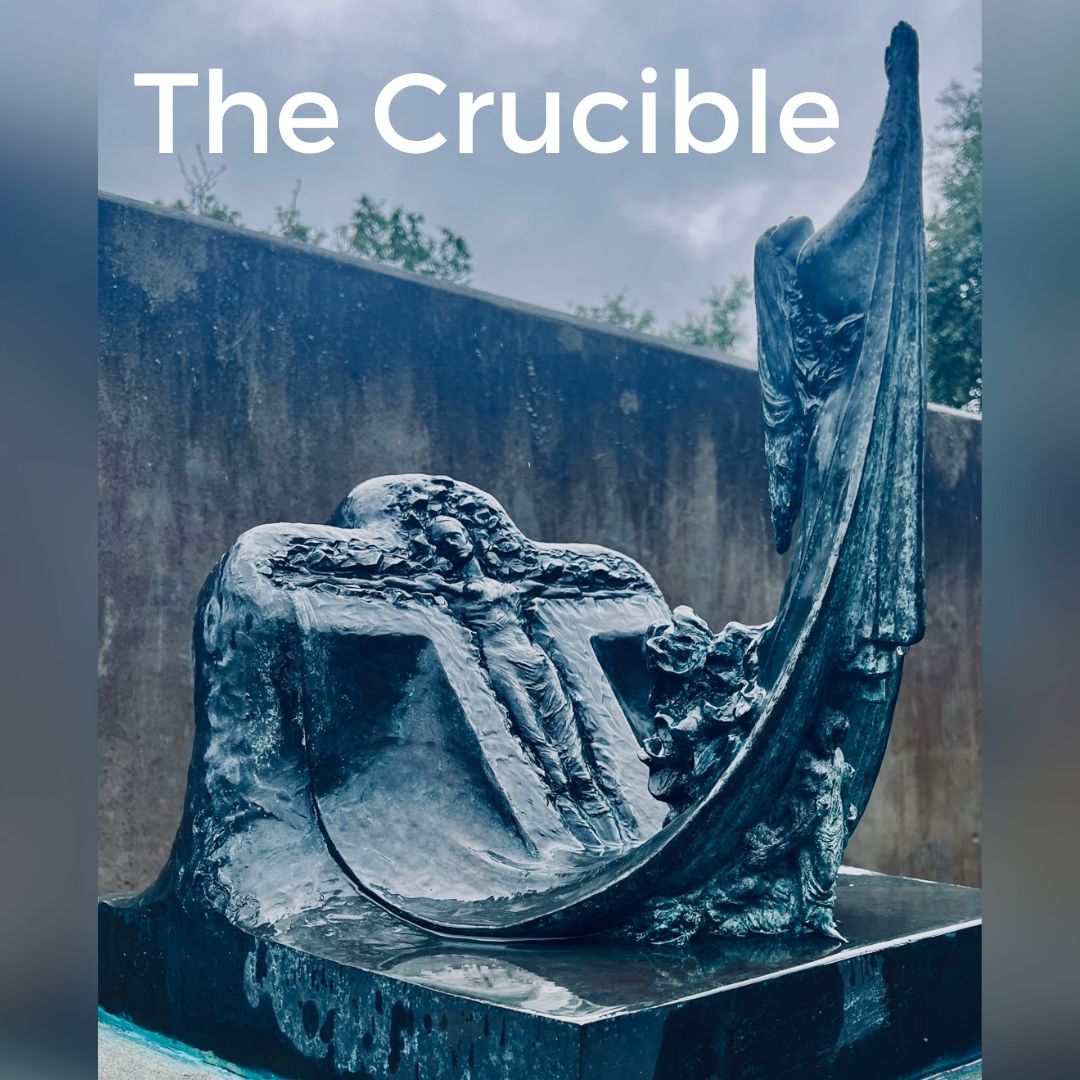

However, if one of the primary purposes of public art is to powerfully express, remind, and inspire us to pursue virtue in our lives, Einar Jonsson’s sculpture called The Crucible is a singular achievement.

The Crucible isn’t one of Jonsson’s larger works, or even one of his more beautiful, but one is hard-pressed to examine it for any length of time amidst the Icelandic birch that surrounds it and not be moved by its profound message in a memorable way.

The weight of the sculpture is at the back, derived from the shape of a heavy cross with the figure of a human being—a bereaved woman inside. Her arms are outstretched, her head downturned in suffering within the crucible of the cross. However, at the bottom of this shape, the bronze begins to turn, curving upward and into a second form—possibly an angel or perhaps the same woman transformed, her body soaring, her hands reaching skyward in joyous, energetic prayer. The sculpture legibly expresses a narrative: one that says to rise we must take on the cruciform shape Christ took on—one of suffering service, one of love, one of loss.

The human struggle, Jonsson’s work tells us, is hard. It’s painful. It’s heavy. But it’s also heroic and virtuous and rewarding. And the trials we encounter, the challenges we face, have the power, in Christ, to elevate us, to raise us, to traject us—as sure as the metal in which this remarkable sculpture is cast—into ascent. Eternal ascent.

God—May I live a cruciform life…and rise.

— Greg Funderburk